============================== Since the introduction of RLHF (40) there have been a number of algorithms developed to tune large models trained via unsupervised learning to better follow instructions and generally align their generations to user preferences (41, 42, 95, 96). We use IRPO (Iterative Reasoning Preference Optimization) due to its simplicity in implementation and good performance. The IRPO loss combines supervised finetuning with contrastive learning from preference pairs.

IRPO is an algorithm used to improve the performance of large models trained through unsupervised learning. It is designed to align the model's output with user preferences by tuning the model's parameters. IRPO combines supervised finetuning with contrastive learning from preference pairs to achieve this goal.

The algorithm operates on a dataset consisting of a prompt and a pair of completions, one preferred and one not preferred. It also uses two separate models: the reference model and the current model. The reference model is a fixed base model of the same scale, while the current model is the model being optimized.

IRPO works by iteratively updating the parameters of the current model to better align with the user's preferences. It does this by computing a loss function that combines supervised finetuning with contrastive learning. The supervised finetuning component of the loss function encourages the model to generate completions that are similar to the preferred completion, while the contrastive learning component encourages the model to generate completions that are different from the not preferred completion.

Overall, IRPO is a simple and effective algorithm for improving the performance of large models trained through unsupervised learning. Its use of supervised finetuning and contrastive learning allows it to align the model's output with user preferences and generate more accurate and relevant completions.

$$ \begin{align} \mathcal{L}{\mathrm{IRPO}}\left(\pi{\theta} ;\right. & \left.\pi{\mathrm{ref}}\right)=\mathcal{L}{\mathrm{NLL}}+\alpha \mathcal{L}{\mathrm{DPO}}= \ & -\mathbb{E}{\left(x, y{w}, y{l}\right) \sim \mathcal{D}}\left[\frac{\log \pi{\theta}\left(y{w} \mid x\right)}{\left|y{w}\right|+|x|}+\right. \ \alpha \log \sigma & \left.\left(\beta \log \frac{\pi{\theta}\left(y{w} \mid x\right)}{\pi{\mathrm{ref}}\left(y{w} \mid x\right)}-\beta \log \frac{\pi{\theta}\left(y{l} \mid x\right)}{\pi{\mathrm{ref}}\left(y_{l} \mid x\right)}\right)\right] \tag{2} \end{align}

The equation (2) defines the Information Ratio Policy Optimization (IRPO) loss function, which is a combination of the Negative Log-Likelihood (NLL) loss and the Divergence Penalty Objective (DPO) loss. The NLL loss is a standard loss function used in machine learning to measure the difference between the predicted and true probabilities of the data. The DPO loss is a regularization term that encourages the model to produce diverse and informative predictions by penalizing the divergence between the predicted and reference distributions.

The IRPO loss function takes as input the predicted distribution $\pi\theta$ and the reference distribution $\pi\mathrm{ref}$, and outputs a scalar value that measures the performance of the model. The first term in the equation is the NLL loss, which is defined as the negative expected log-likelihood of the predicted distribution given the data. The second term is the DPO loss, which is defined as the divergence between the predicted and reference distributions, weighted by a hyperparameter $\alpha$. The DPO loss encourages the model to produce diverse and informative predictions by penalizing the divergence between the predicted and reference distributions.

The IRPO loss is a combination of two terms: the $\mathcal{L}{\text {NLL }}$ term and the $\mathcal{L}{\text {DPO }}$ term. The $\mathcal{L}{\text {NLL }}$ term maximizes the log likelihood of the preferred example normalized by the length of the sequence, which helps to reinforce the good generations from the model. The $\mathcal{L}{\text {DPO }}$ term is the contrastive preference tuning term, which increases the difference in log likelihoods between the preferred and not preferred examples while staying close to the reference model. This helps to prevent overfitting to the preference dataset, which can often be small.

There are two hyperparameters, $\alpha$ and $\beta$. $\alpha$ controls the relative importance of the supervised with the preference loss, while $\beta$ controls how close we stay to the reference model. The higher the beta, the closer we stay to the reference model. We minimize this loss with respect to the current model parameters $\theta$.

ESM3 is a multi-modal model that can take in various input tracks such as partial sequence, structure, and function, and generate output tracks such as amino-acid sequence. In the experiments, the focus is on generating the amino-acid sequence. However, computing the full likelihood of generating the sequence from the prompt involves integrating over all possible multi-step decoding paths, which is intractable. Therefore, a surrogate is used that mirrors pre-training, as shown in Eq. (3) and described below.

$$ \begin{equation} \log \pi(y \mid x) \approx \mathbb{E}{m}\left[\sum{i \in m} \log p\left(y{i} \mid y{\backslash m}, x\right)\right] \tag{3} \end{equation}

To estimate the probability of generating a response $y$ given a prompt $x$, we use a technique called linear noise schedule masking. This involves randomly selecting a mask from a linear noise schedule and applying it to $y$. We then use a language model called ESM3 to generate a set of logits for $y$ and $x$. Finally, we calculate the cross-entropy between the logits and the masked positions of $y$.

During training, we use the same mask to calculate the likelihoods for the reference policy and the current policy, as well as for the preferred sample and the non-preferred sample. This helps us to optimize the model and improve its performance.

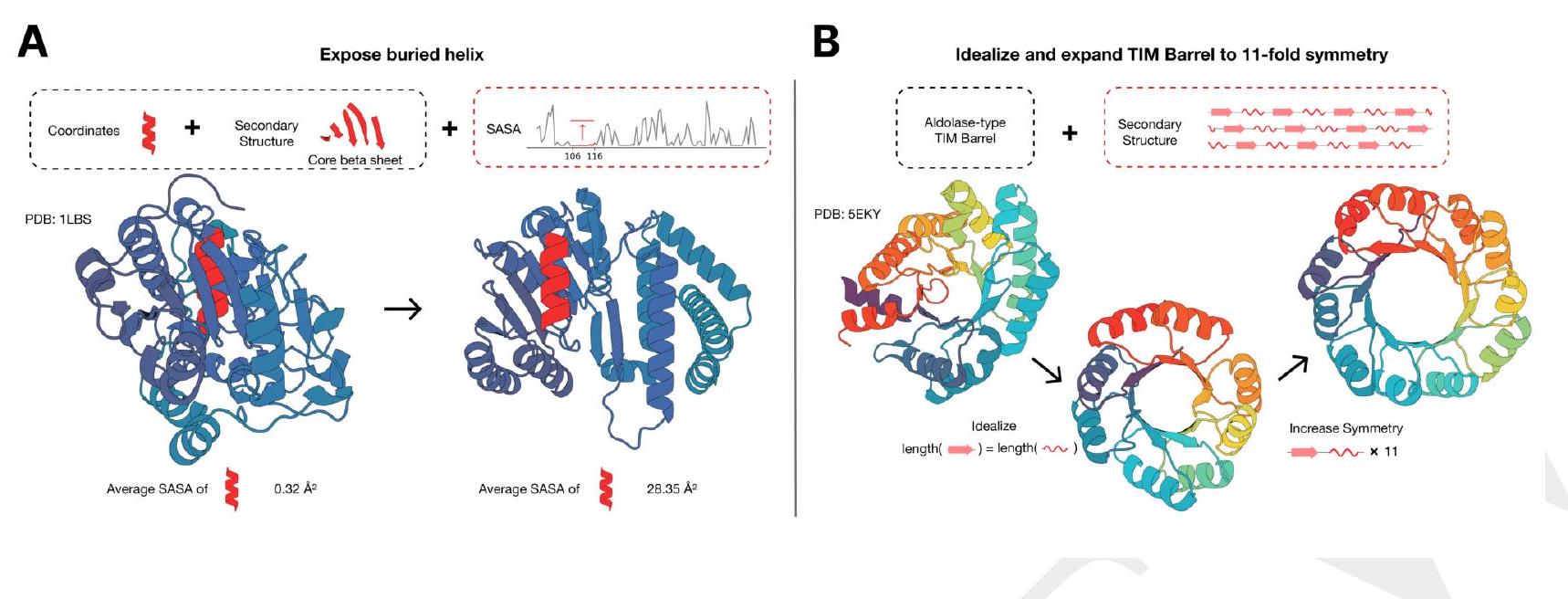

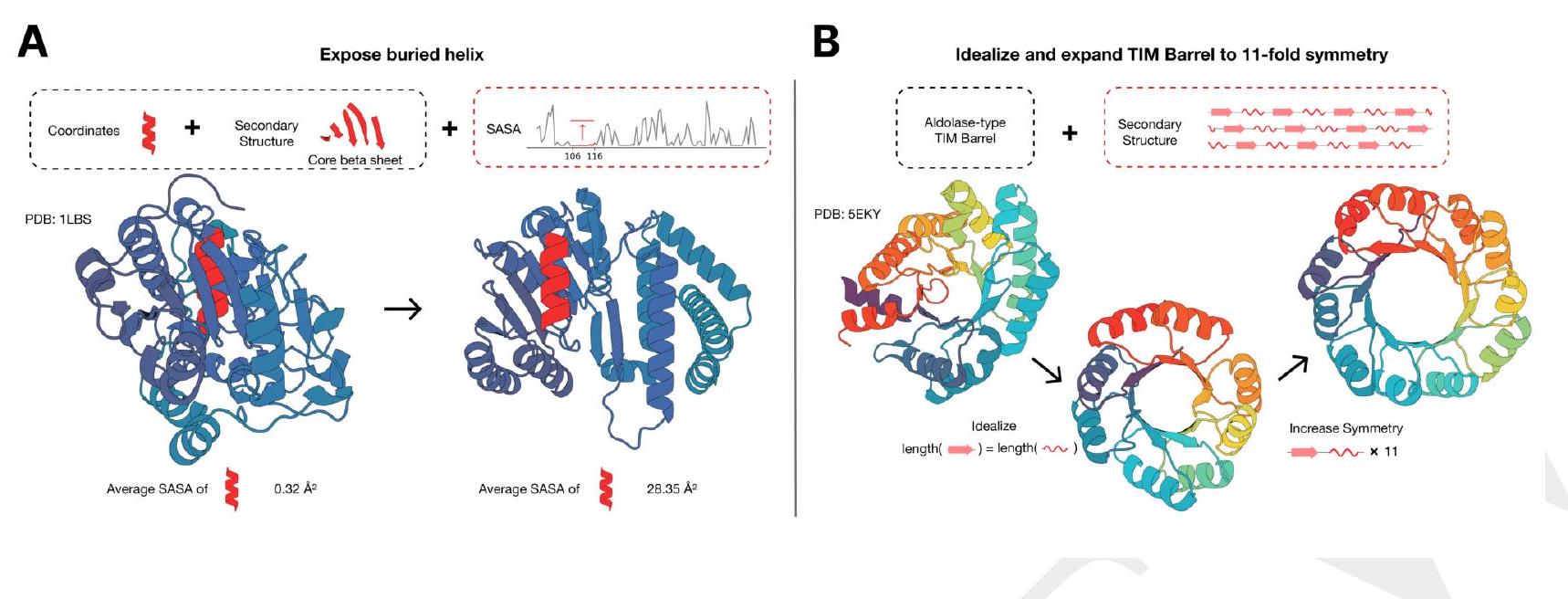

The figure shows the use of ESM3, a protein editing tool, to modify the structure of a protein. In the first step, ESM3 is used to expose a buried helix in the protein while maintaining the overall fold of the protein. This is achieved by using a combination of secondary structure prompting and function prompting.

In the second step, ESM3 is used in a two-step iterative edit to modify the protein further. First, secondary structure prompting is used to idealize a reference TIM barrel, which is a common protein fold. Then, secondary structure prompting is used again to increase the number of subunits in the TIM barrel from 8 to 11.

Overall, the figure demonstrates the versatility of ESM3 in modifying protein structures and highlights its potential for use in protein engineering and design.

Rearranging the DPO term of the loss function gives some insight into how it finetunes the model for the preference pairs. $$ \begin{align} \mathcal{L}{\mathrm{DPO}}\left(\pi{\theta} ;\right. & \left.\pi{\mathrm{ref}}\right)= \ & \mathbb{E}{\left(x, y{w}, y{l}\right) \sim \mathcal{D}}\left[-\log \sigma\left(-\beta z{\theta}\left(x, y{l}, y{w}\right)\right)\right] \tag{4} \end{align} $$ where $$ \begin{aligned} z{\theta}\left(x, y{l}, y{w}\right) & =\log \frac{\pi{\theta}\left(y{l} \mid x\right)}{\pi{\mathrm{ref}}\left(y{l} \mid x\right)}-\log \frac{\pi{\theta}\left(y{w} \mid x\right)}{\pi{\mathrm{ref}}\left(y{w} \mid x\right)} \ & =\log \frac{\pi{\mathrm{ref}}\left(y{w} \mid x\right)}{\pi{\mathrm{ref}}\left(y{l} \mid x\right)}-\log \frac{\pi{\theta}\left(y{w} \mid x\right)}{\pi{\theta}\left(y{l} \mid x\right)} \end{aligned}

The DPO (Differential Preference Ordering) loss function is used to fine-tune a model for preference pairs. It does this by rearranging the DPO term of the loss function, which gives insight into how the model is being optimized.

The DPO loss function is defined as the negative log of the sigmoid function applied to the difference between the log probabilities of the reference model and the current model for the preference pairs. The preference pairs consist of a labeled example (yl) and an unlabeled example (yw) for each input (x).

By rearranging the DPO term, we can see that the loss function is trying to maximize the difference between the log probabilities of the reference model and the current model for the preference pairs. This means that the model is being optimized to better distinguish between the labeled and unlabeled examples for each input.

In summary, the DPO loss function is used to fine-tune a model for preference pairs by maximizing the difference between the log probabilities of the reference model and the current model for the preference pairs. This helps the model better distinguish between labeled and unlabeled examples for each input.

The function $f(z)=-\log \sigma(-\beta z)=\log (1+\exp (\beta z))$ is the softplus function, and is an approximation of the hinge function; in other words $f(z)=\beta z$ when $z>>0$ and $f(z)=0$ when $z \ll 0$. Because of this property, there are two cases. In the case where $$ \begin{equation} \log \frac{\pi{\mathrm{ref}}\left(y{w} \mid x\right)}{\pi{\mathrm{ref}}\left(y{l} \mid x\right)}>>\log \frac{\pi{\theta}\left(y{w} \mid x\right)}{\pi{\theta}\left(y{l} \mid x\right)} \tag{5} \end{equation} $$ $f(z)$ is in the linear regime, so the loss function is simply maximizing the likelihood ratio $\log \frac{\pi{\theta}\left(y{w} \mid x\right)}{\pi{\theta}\left(y{l} \mid x\right)}$. In the case where $$ \begin{equation} \log \frac{\pi{\text {ref }}\left(y{w} \mid x\right)}{\pi{\text {ref }}\left(y{l} \mid x\right)} \ll \log \frac{\pi{\theta}\left(y{w} \mid x\right)}{\pi{\theta}\left(y{l} \mid x\right)} \tag{6} \end{equation} $$

The softplus function, denoted as $f(z)$, is a function that is commonly used in machine learning and neural networks. It is defined as $f(z) = \log(1 + e^{\beta z})$, where $\beta$ is a positive constant. This function is an approximation of the hinge function, which is a step function that returns $\beta z$ when $z >> 0$ and $0$ when $z \ll 0$.

There are two cases to consider when using the softplus function. In the first case, when $\log \frac{\pi{\mathrm{ref}}\left(y{w} \mid x\right)}{\pi{\mathrm{ref}}\left(y{l} \mid x\right)} >> \log \frac{\pi{\theta}\left(y{w} \mid x\right)}{\pi{\theta}\left(y{l} \mid x\right)}$, the softplus function is in the linear regime. This means that the function is approximately equal to $\beta z$, and the loss function is simply maximizing the likelihood ratio $\log \frac{\pi{\theta}\left(y{w} \mid x\right)}{\pi{\theta}\left(y{l} \mid x\right)}$.

In the second case, when $\log \frac{\pi{\mathrm{ref}}\left(y{w} \mid x\right)}{\pi{\mathrm{ref}}\left(y{l} \mid x\right)} \ll \log \frac{\pi{\theta}\left(y{w} \mid x\right)}{\pi{\theta}\left(y{l} \mid x\right)}$, the softplus function has saturated. This means that the function is approximately equal to $0$, and the loss function is designed to ensure that we do not deviate too far from the reference model.

Overall, the softplus function is a useful tool in machine learning and neural networks, as it allows us to approximate the hinge function and optimize our models accordingly.

Certainly! In the context of ESM3 finetuning, the dynamics refer to the behavior of the loss function as it interacts with the surrogate likelihood. The surrogate likelihood is used as a substitute for the true likelihood, which is often computationally expensive to calculate. The loss function is used to measure the difference between the predicted and actual values of the data.

During the finetuning process, the loss function is used to adjust the parameters of the model in order to improve its performance. As the model is adjusted, the surrogate likelihood is also updated to reflect the changes in the model.

The dynamics of the loss function and surrogate likelihood are such that the loss function will increase the surrogate of the preferred pair over the non-preferred pair. This means that the model will be adjusted to better fit the preferred pair of data points, while the non-preferred pair will be less well-fit.

However, there is a limit to how much the model can be adjusted before it deviates too much from the reference model. At this point, the loss function will start to increase, indicating that the model is no longer improving.

To an expert, the most important aspect of preference tuning is determining how to categorize generations based on preferences. The primary goals are to ensure the quality and correctness of the generated sequence. Quality refers to the stability of the sequence as a protein, while correctness pertains to how well the sequence adheres to the given prompt. This section specifically addresses structure coordinate prompts, and prompt consistency can be evaluated using constrained site RMSD (cRMSD), which measures the RMSD between the prompt coordinates and the corresponding coordinates in the predicted structure of the generated sequence. Sequence quality can be assessed using predicted-TM (pTM) of a structure predictor on the generated sequence.

As an expert, you are aware that metrics are used to evaluate the performance of a model. However, there is a risk of over-optimizing the metric, which can lead to a model that performs well on the metric but not on the actual property of interest. In the case of pTM, which is a structure predictor, there is a risk of over-optimizing the metric and losing correlation with the actual property of interest, which is the viability of the sequence to be a stable protein.

To mitigate this risk, it is recommended to use orthogonal models to rank the training dataset and to perform evaluation. This means using models that are different from the one being evaluated to rank the training dataset. This helps to ensure that the model is not over-optimized for the specific metric and that it is still able to perform well on the actual property of interest.

In summary, using orthogonal models to rank the training dataset and to perform evaluation can help to mitigate the risk of over-optimizing a metric and losing correlation with the actual property of interest.

To create the training datasets, generations are evaluated according to cRMSD and pTM of ESM3 7B to maintain a consistent structure predictor across all datasets. After the preference tuning phase, the generations from the tuned models are evaluated with ESMFold cRMSD and pTM as

To develop training datasets, the generations are assessed based on cRMSD and pTM of ESM3 7B to ensure a consistent structure predictor across all datasets. After the preference tuning phase, the generations from the tuned models are evaluated using ESMFold cRMSD and pTM as an orthogonal model. By training on ESM3 derived metrics and evaluating on ESMFold derived metrics, the risk of over optimization for adversarial generations can be reduced.

The ESM3 model scales are trained using the IRPO loss function on their respective preconstructed training datasets. These datasets consist of structure coordinate prompts and generations of various difficulty, with 16 generations each for 30,000 prompts from the respective ESM3 model. The preference selection is determined by a threshold of metrics, where a sample is considered "good" if it has an ESM3 7B pTM greater than 0.8 and a backbone cRMSD to its structure prompt less than 1.5 Å.

This explanation is related to the process of creating preference pairs for a prompt. A "good" sample is paired with a "bad" sample to create a preference pair. To ensure that the "bad" sample is truly different from the "good" sample, there must be a gap between their metrics. This gap is enforced by requiring that the delta pTM (delta predicted melting temperature) is at least 0.2 and the delta backbone RMSD (root mean square deviation) is less than -2 Å. If a prompt has no valid preference pairs, it is discarded.

The structure prompts are a set of proteins that have been modified from our pre-training pipeline. Half of these prompts are synthetic active sites, while the other half are structure coordinates that have been randomly masked with a noise schedule. All of the structure prompts are derived from PDB structures that were created before May 1st, 2020.

The synthetic active sites are created by identifying sequences from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) that have coordinating residues. These sequences are then used to generate the synthetic active sites. The amino acid identities of these sequences are included in the prompt to provide information about the specific residues that are involved in the coordination. This information is useful for experts who are analyzing the structure and function of the active sites.

The remaining structure track prompts are being hidden or obscured according to a cosine noise schedule. This means that the prompts are being altered in a way that follows a specific pattern or schedule, which is based on a cosine function.

Half of the noise scheduled prompts are being masked in completely random positions, meaning that they are being hidden or obscured in a way that is not predictable or patterned. The other half of the noise scheduled prompts are being masked according to an autocorrelation mechanism, which means that they are being hidden or obscured in a way that is related to the previous prompt's position. This autocorrelation mechanism prefers sequentially masked positions, meaning that it is more likely to mask prompts that are in a sequence or pattern.

This explanation is related to the process of training a language model using iterative decoding. The training dataset for each model is generated from its own reference model, which means that the model is trained on its own previous generations.

When generating samples for a given prompt, the model uses iterative decoding with $L / 4$ steps, where $L$ is the length of the prompt. This means that the model generates a sequence of tokens, and then uses the previous tokens as input to generate the next token in the sequence. This process is repeated for $L / 4$ steps, where $L$ is the length of the prompt.

During the iterative decoding process, the temperature is annealed from 1.0 to 0.5 over the decoding steps. This means that the model starts with a high temperature, which encourages exploration of the search space, and gradually lowers the temperature, which encourages exploitation of the most promising paths in the search space.

The task of atomic coordination involves creating proteins that meet specific tertiary interaction constraints. This requires the identification of residues that are close in 3D space but far apart in sequence. To evaluate the performance of this task, a dataset of 46 proteins with ligand binding sites from the Biolip dataset was curated. These proteins were selected after the training set cutoff date and were deposited in the PDB. The coordinating residues used in the model were defined by the ligand binding sites in the Biolip dataset.

ESM3 is a software tool that can generate novel protein structures by applying multiple transformations to a given prompt. The prompt consists of the sequence and coordinates of the residues for a particular ligand binding site. The total sequence length is sampled evenly to be 150, 250, or 350 residues, regardless of the original sequence length.

To define the coordinating residues, ESM3 identifies prompt residues with fewer than 5 sequence positions between them. The order and distance between contiguous spans of residues are then shuffled to ensure that the original protein will no longer satisfy the prompt.

A generation is considered a success if the backbone cRMSD is less than 1.5 Å and the pTM is greater than 0.8. The backbone cRMSD measures the root mean square deviation of the backbone atoms between the generated structure and the original structure, while the pTM is a measure of the protein's thermodynamic stability.

To evaluate the performance of a model, we generate a total of 1024 prompts for each ligand and generate a completion for each prompt using the model. We then report Pass@ 128, which is an estimate of the fraction of ligands with at least one successful completion after 128 prompts per ligand. This estimate is obtained using an unbiased estimator proposed by Chen et al. (98) on Page 3, which takes into account the success rate over 1024 prompts.

To visualize the performance of the model, we randomly select successful generations for both the base model and finetuned model and display them in Fig. S18. This allows us to compare the quality of the generated completions and assess the effectiveness of the finetuning process.

To evaluate the effectiveness of preference tuning, we compare it to a supervised finetuning (SFT) baseline. In the SFT baseline, we train the model to increase the likelihood of high-quality samples without using the preference tuning loss. We find that the preference tuned models outperform the SFT baseline in terms of solving atomic coordination tasks. Specifically, the 1.4B, 7B, and 98B models solve 14.2%, 33.7%, and 44.6% of atomic coordination tasks at 128 generations, respectively. While these results are an improvement over the base models, they are still much lower than the corresponding preference tuned versions. Therefore, preference tuning is a valuable technique for improving the performance of language models in solving complex tasks.

The IRPO model is trained using the RMSProp algorithm for 1000 steps. The learning rates used for the 1.4B, 7B, and 98B models are $1 \mathrm{e}-5,1 \mathrm{e}-5$, and $5 \mathrm{e}-6$, respectively. These learning rates are annealed using a cosine schedule after a 150 step warmup. Additionally, gradient norms are clipped to 1.0.

For all IRPO runs $\beta=0.05$ and $\alpha=0.8$. The SFT baseline uses the same hyperparameters, but with $\alpha=0.0$ to disregard the preference tuning term.

The statement is describing the hyperparameters used in a specific algorithm or model, specifically the IRPO (Importance-Weighted Reinforcement Learning with Preference-Based Advice) algorithm and the SFT (Softmax Function Tuning) baseline. The hyperparameters $\beta$ and $\alpha$ are used to control the balance between exploration and exploitation in the algorithm.

In the IRPO algorithm, $\beta=0.05$ and $\alpha=0.8$ are used. This means that the algorithm will have a relatively high exploration rate (controlled by $\beta$) and a relatively high exploitation rate (controlled by $\alpha$). This is because the algorithm is designed to incorporate both exploration and exploitation in order to learn from both the agent's own experiences and the advice of an external advisor.

In the SFT baseline, the same hyperparameters are used, but with $\alpha=0.0$. This means that the algorithm will have a very low exploitation rate, as the preference tuning term is disregarded. This is because the SFT baseline is designed to focus solely on exploration, without incorporating any external advice or preferences.

Overall, the choice of hyperparameters in these algorithms is important for achieving the desired balance between exploration and exploitation, and for incorporating external advice or preferences as needed.