We are releasing the ESM3 source code and model weights of an open model, ESM3-open. ESM3-open is a 1.4Bparameter model we trained without OAS antibody sequences and with precautionary risk mitigations for release to the academic research community.

As part of this release, we follow guidance from the Principles for the Responsible Development of AI for Biological Design (107). We adopted precautionary risk mitigations, described in Appendix A.6.1, and performed risk evaluations, detailed in Appendix A.6.2. Additionally we conducted a review of the risks and benefits of releasing ESM3-open with experts from the scientific community. We provided reviewers access to ESM3-open, along with a detailed technical report on our risk evaluations. We received unanimous feedback from our reviewers that the benefits of releasing the model greatly outweigh any potential risks.

We see this release as a first step and plan to work with the scientific community to continue to improve processes around responsible development. Open models enable the scientific community to better understand and reduce any potential risks of biological design tools. As our understanding develops alongside the capabilities of future models, we plan to continuously improve our evaluation frameworks, safeguards, and mitigation strategies.

As a precaution, we filtered the training data of ESM3-open to minimize model performance on sequences of potential concern while otherwise maintaining performance. We also removed the capability for the model to follow prompts related to viruses and toxins.

Filtering sequences of potential concern. Previous work has shown that the performance of protein language models is closely related to the number of similar sequences present in the training data (5). We therefore removed sequences aligned to potentially-concerning proteins from the training data in order to reduce the capability of ESM3-open on these sequences.

We identified and removed sequences unique to viruses, as well as viral and non-viral sequences from the Select Agents and Toxins List (108) maintained by the CDC and USDA. The U.S. Department of Health \& Human Services recommends filtering based on the Select Agents list as part of their Screening Framework Guidance for Providers and Users of Synthetic Nucleic Acids (109).

\begin{tabular}{|c|c|c|c|} \hline Protein & \begin{tabular}{l} Sequence \ Identity to \ esmGFP \end{tabular} & \begin{tabular}{l} Mutations \ to esmGFP \end{tabular} & Aligned Sequence \ \hline B8 & 0.93 & 15 & \begin{tabular}{l} -MSKVEELIKPEMKMKLEMEGEVNGHKFSIEAEGEGKPYEGKQTIKAWSTT-GKLPAW \ DILSTSLTYGFRMFTKYPEGLEEHDYFKQSFPEGYSWERTITYEDGATKVTSDISLED \ GVLINKIKFKGTNFPSDGPVM-QKKTTGEEPSELITPDPATGGLKGEVKMRLKLEGGG \

\end{tabular} \ \hline esmGFP & 1.0 & 0 & \begin{tabular}{l} -MSKVEELIKPDMKMKLEMEGEVNGHKFSIEAEGEGKPYEGKQTIKAWSTT-GKLPFAW \ DILSTSLTYGNRAFTKYPEGLEQHDFFKQSFPEGYSWERTITYDGAAVKVTADISLED \ GVLINKVKFKGENFPSDGPVM-QKKTTGEEASTELITPDATGGLKGEVKMRLKLEGGG \

\end{tabular} \

\hline tagRFP & 0.58 & 96 & \begin{tabular}{l}

MVSKGEELIKENMHMKLYMEGTVNNHHFKCTSEGEGKPYEGTQTMRIKVVEGGPLPFAF \

DILATSFMYGSRTFINHTQGIP--DFEKQSFEEGTWERVVTYEDGGVLTATQDTSLQD \

GCLIYNVKIRGVNEPSNGPVM-QKKTLGWEANTEMLY--PADGGLEGRTDMALKLVGGG \

HLICNFKTTYRSKKPAKNLKMPGVYYVDHRL--ERIKEADKETYVEQHEVAVARYCDLP \

SKLGHKLN

\end{tabular} \

\hline eqFP578 & 0.53 & 107 & \begin{tabular}{l}

----MSELIKENMHMKLYMEGTVNNHHFKCTSEGERKPYEGTQTMKIKVVEGGPLPFAF \

DILATSFMYGSKTFINHTQGIP-DDLFKQSFEEGTWERITTYEDGGVLTATQDTSLQN \

GCIIYNVKINGVNFPSNGSVM-QKKTLGWEANTEMLY--PADGGLRGHSQMALKLVGGG \

YLHCSFKTTYRSKKPAKNLKMPGFHFVDHRL--ERIKEADKETYVEQHEMAVAKYCDLP \

SKLGHR--

\end{tabular} \

\hline template & 0.38 & 112 & \begin{tabular}{l}

-MSKGEELFTGVVPILVELDGDVNGHKFSVSGEGEGDATYGKLTLKFICTT-GKLPVPW \

PTLVTTLTYGVQCFSRYPDHMKQHDFKSAMPEGYVQERIISKDDGNYKTRAEVKFEG \

DTLVNRIELKGIDFKEDGNILGHKLEYNYNSHNVYITADKQKNGIKANFKIRHNIEDGS \

VQLADHYQQNTPIGDGP-VLLPDNHYLSTQSALSKDPN-EKRDHMVLLEFVTAAGI--

\end{tabular} \

\hline avGFP & 0.36 & 146 & \begin{tabular}{l}

-MSKGEELFTGVVPILVELDGDVNGHKFSVSGEGEGDATYGKLTLKFICTT-GKLPVPW \

PTLVTTFSYGVQCESRYPDHMKQHDFFKSAMPEGYVEERTIFKRDGNYKKRAEVKFEG \

DTLVNRIELKGIDFKEDGNILGHKLEYNYNSHNYYMADKQKNGIKVNFKIRHNIEDGS \

VQLADHYQQNTPIGDGP-VLLPDNHYLSTQSALSKDPN-EKRDHMVLLEFVTAAGITHG \

MDELYK--

\end{tabular} \

\hline

\end{tabular}

Table S14. Multiple sequence alignment of select GFP designs (B8, esmGFP) and reference proteins. Template is the full sequence of our template structure (PDB ID 1QY3), with chromophore slowing mutation A96R removed. tagRFP is the full sequence of the top hit returned by BLAST search of the nonredundant database $\mathrm{n} r$, avGFP and eqFP578 are from FPBase. Sequence identities for GFP designs are in general calculated as the number of non-gap matches at aligned positions, divided by the minimum length of the query and target ungapped sequences. Here, only sequence identities to esmGFP are shown. Similarly, the number of mutations to esmGFP are calculated as the number of mismatches at aligned positions where esmGFP does not have a gap.

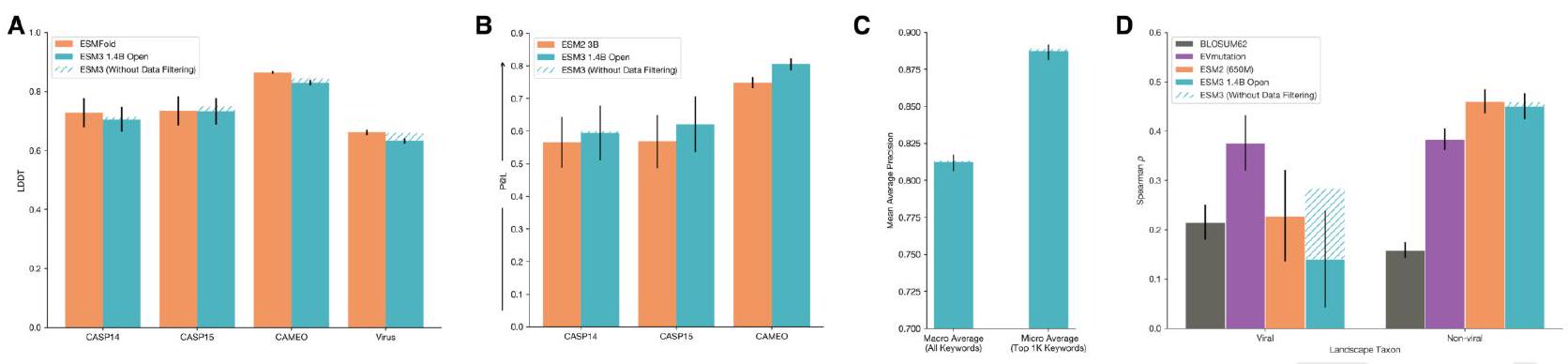

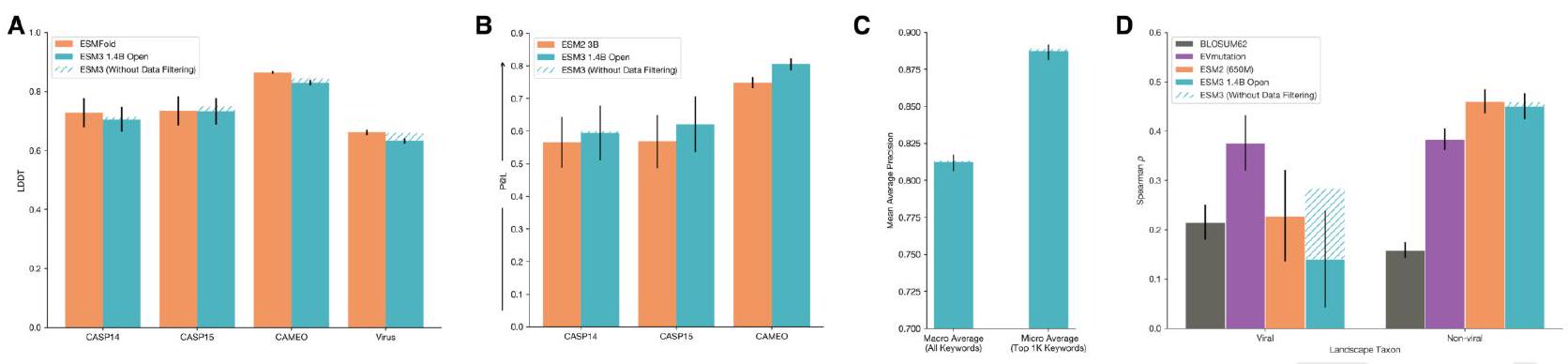

Figure S23. ESM3-open is a powerful predictor of structure and function trained for open release. A: Structure Prediction ESM3open (blue) is competitive with ESMFold (orange) on structure prediction as measured by LDDT on CAMEO and CASP14/15. See Appendix A.3.4 for details on this evaluation. B: Representation Learning ESM3-open (blue) is competitive with ESM2-3B (orange) on representation learning as measured by contact prediction $\mathrm{P} @ \mathrm{~L}$ for finetuned representations. See Appendix A.3.3 for details on this evaluation. C: Function Keyword Prediction. ESM3-open function prediction performance, as measured by Mean Average Precision across function keywords. ESM3-open achieves 0.81 precision across all keywords, and 0.89 for the top $1 \mathrm{~K}$ most prevalent keywords in the validation set (CAMEO). We use the same evaluation framework as in Appendix A.1.8.2.2. We report both the macro and micro averages as in Fig. S8. In each of the preceding evaluations, the data mitigation minimally impacted performance, as compared to a compute-matched model without data mitigations (hatched blue). D: Zero-shot Fitness Prediction. Fitness prediction performance as measured by correlation (Spearman $\rho$ ) across 217 Deep Mutational Scanning datasets collated in ProteinGym. Left and right subplots indicate viral (left) and non-viral (right) DMS datasets. The four columns per group indicate different models. ESM3-open performs substantially worse than EVMutation (purple) on viral fitness prediction, while being competitive with ESM2 (orange) on non-viral fitness prediction. Viral fitness prediction was substantially impacted by the data mitigation, while non-viral fitness prediction was not (hatched blue).

To filter data, we create two denylists: the Viral Denylist and the Select Agent Denylist. We then remove all sequences from the training set that are detected to align to those in the denylists by MMseqs2 at or above a given sequence identity threshold.

To create the Viral Denylist, we identify $\sim 4 \mathrm{M}$ sequences that are annotated as viral in UniProt and align almost exclusively to other viral sequences in UniProt. This gives us a procedure that removes viral proteins with both high sensitivity and specificity (as measured by UniProt taxonomic annotations). To create the Select Agents Denylist we identify all sequences in UniProt belonging to organisms on the Select Agents and Toxins List (108). This process gives us $147 \mathrm{~K}$ non-viral sequences and $40 \mathrm{~K}$ additional viral sequences.

For each denylist, MMseqs was used to query against the full set of training databases, (including PDB, UniRef, MGnify, and JGI) and all hits were removed from the training set. This filter removes a total of $10.6 \mathrm{M}$ sequences across all training sets.

Removal of keywords of concern. There are a number of keyword prompts associated with viruses and toxins that we aim to remove. We first identify a list of harmful keywords with the following steps:

Of the original 68,103 keywords that ESM3 is trained with, this filter removes a total of 9,462 (14\%), creating a new vocabulary of 58,641 keywords.

The function vocabulary is defined via vectors representing Term Frequency Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) which are then tokenized using Locality Sensitive Hashing (LSH), as previously described in Appendix A.1.8. To remove flagged keywords, they are first removed from the TF-IDF vocabulary by removing the entries corresponding to flagged keywords. This reduces the TF-IDF vector size to 58,641 . The LSH tokenization is defined by 64 hyperplanes, each defined in the TF-IDF space, i.e. a Euclidean space with one dimension per keyword. We redefine the hyperplanes to be in the reduced space by removing the dimensions corresponding to the flagged keywords. This per- manently removes the information required for tokenization of the flagged keywords. This mitigation is highly selective and does not change the tokenization for any non-flagged keywords.

\section*{A.6.2. ESM3-open Evaluations}

In the section below, we outline our evaluations of ESM3open performance. When appropriate, we compare ESM3open to either existing open models, (e.g. ESM2 or ESMFold), or to a compute-matched version of ESM3-open, trained without any data mitigations.

Structure Prediction In Fig. S23A, we show that ESM3open achieves competitive performance on structure prediction as measured by LDDT on CASP14, 15 and CAMEO, showing very slight degradation from our compute-matched 1.4B model without data filtering. The evaluation framework is described in Appendix A.3.4.

We also measure the ability of ESM3 to predict the structure of a subset of viral proteins. In Fig. S23A we evaluate structure prediction on a set of structures derived from viruses that were purged from the PDB training set. For the chains in PDB that were $>70 \%$ sequence identity hits to the Viral Denylist, we cluster at $40 \%$ sequence identity and then select the longest chain (with length $\leq$ 1024) from each cluster. ESMfold and ESM3-open achieved an average LDDT of 0.66 and 0.63 , respectively, on the viral structures. Without the data mitigation, a compute-matched ESM3-open would have achieved an average LDDT of 0.66. This is substantially worse than the performance on generic structure prediction on CAMEO, and CASP14, where ESMFold achieved an average LDDT of 0.86 and 0.73, and ESM3open achieved an average of LDDT of 0.83 and 0.70.

Representation Learning. ESM3-open achieves strong performance on representation learning, slightly outperforming ESM2 (3B) on contact prediction as measured by precision at $\mathrm{L}(\mathrm{P} @ \mathrm{~L})$ on structures derived from CASP14/15, and CAMEO, see Fig. S23B. The evaluation framework is described in Appendix A.3.3.

Function Keyword Prediction. ESM3-open is able to predict function keywords for proteins in a validation set derived from UniRef and annotated with InterProScan, see Fig. S23C. ESM3-open achieves a Mean Average Precision for all keywords of 0.81 (macro average), and a precision of 0.89 (micro average) for the top 1000 keywords, discarding common terms such as "the". The evaluation framework is the same as that described in Appendix A.1.8.2.2.

Zero-shot Viral Fitness Prediction. We measure the ability of ESM3 to identify viable sequences and understand the effects of mutations on viral proteins. The evaluation consists of the single mutant variants from 217 Deep Mutational Scanning (DMS) datasets collected in ProteinGym (110). This includes 28 DMS landscapes from viral proteins and 189 from other proteins. We evaluate the correlation (Spearman $\rho$ ) between the predicted variant effect and measured variant effect. The predicted variant effect is measured as the difference between the logit value for the variant allele and the logit value of the wildtype allele at a given masked position (16).

First, we compare the performance of ESM3-open to a compute-matched version of ESM3-open which did not undergo any data filtering. Applying data filtering as a mitigation reduces average Spearman $\rho$ performance on viral fitness prediction from 0.28 (ESM3-small) to 0.17 (ESM3-open), while performance on non-viral proteins is not adversely affected, changing from 0.46 (ESM3-small) to 0.45 (ESM3-open). We also compare the performance of ESM3-open to existing open model baselines. Fig. S23D assesses performance relative to the EVMutation (111) baseline. EVMutation is a Markov Random Field model (not deep learning-based) trained on a multiple sequence alignment of the target protein. BLOSUM62 is a baseline based on amino acid substitution frequencies. After mitigations, ESM3-open performance on viral landscapes is low compared to EVMutation and on-par with BLOSUM62.