==============================

We wanted to know if a pre-trained model called ESM3 could create proteins that work properly. To test this, we tried to make a special type of protein called GFP that glows green. We wanted to make sure it was different from other GFPs that already exist. We chose to make it glow because it's hard to do, easy to see, and really cool!

Explanation: ESM3 is a pre-trained model that we used to generate proteins. GFP stands for green fluorescent protein, which is a type of protein that glows green. We wanted to create a new version of GFP that was different from existing ones. Fluorescence is the ability of a substance to emit light, and it's a difficult property to achieve in proteins. We chose to make our GFP glow green because it's a beautiful and easily measurable example of fluorescence in nature.

GFP chromophore cofactors substrates fluorescence jellyfish coral proteins GFP family genomes molecules cellular structures processes

The GFP family of proteins is responsible for the fluorescence of jellyfish and the vivid colors of coral. These proteins have a unique ability to form a fluorescent chromophore without the need for cofactors or substrates. This property allows scientists to insert the GFP sequence into the genomes of other organisms to visibly label molecules, cellular structures, or processes. This has become a foundational toolkit that is widely used in the biosciences.

The GFP family has been extensively studied and modified through protein engineering, but most functional variants have been found in nature. Scientists have used rational design and machine learning to create GFP sequences with improved properties, such as higher brightness or stability, by making small changes to the original sequence. However, studies have shown that too many random mutations can reduce fluorescence to zero, and introducing too many mutations can also be difficult. Despite this, scientists have been able to introduce up to 40-50 mutations while retaining GFP fluorescence through high throughput experimentation.

In this paragraph, GFP stands for Green Fluorescent Protein, which is a protein that emits green light when exposed to certain wavelengths of light. Protein engineering is the process of modifying proteins to improve their properties or create new functions. Rational design is a method of protein engineering that involves making specific changes to a protein's sequence based on known structural and functional information. Machine learning is a type of artificial intelligence that can analyze large amounts of data to identify patterns and make predictions. High throughput experimentation involves testing many different variants of a protein in a short amount of time to identify the best performing ones.

GFP is a protein that fluoresces, and it is commonly used in biological research as a marker. The process of creating a new GFP involves the materialization of complex biochemistry and physics that underlie its fluorescence. In all GFPs, an autocatalytic process forms the chromophore from three key amino acids in the core of the protein. The unique structure of GFP, a kinked central alpha helix surrounded by an eleven stranded beta barrel, is what allows it to fluoresce.

Obsidian is a note-taking app that allows users to create and organize notes using Markdown syntax. Markdown is a lightweight markup language that enables users to format text using simple symbols and characters. In Obsidian, users can create internal links between notes by enclosing the note title in double brackets. For example, Obsidian is an internal link to a note titled "Obsidian". This feature allows users to easily navigate between related notes and ideas.

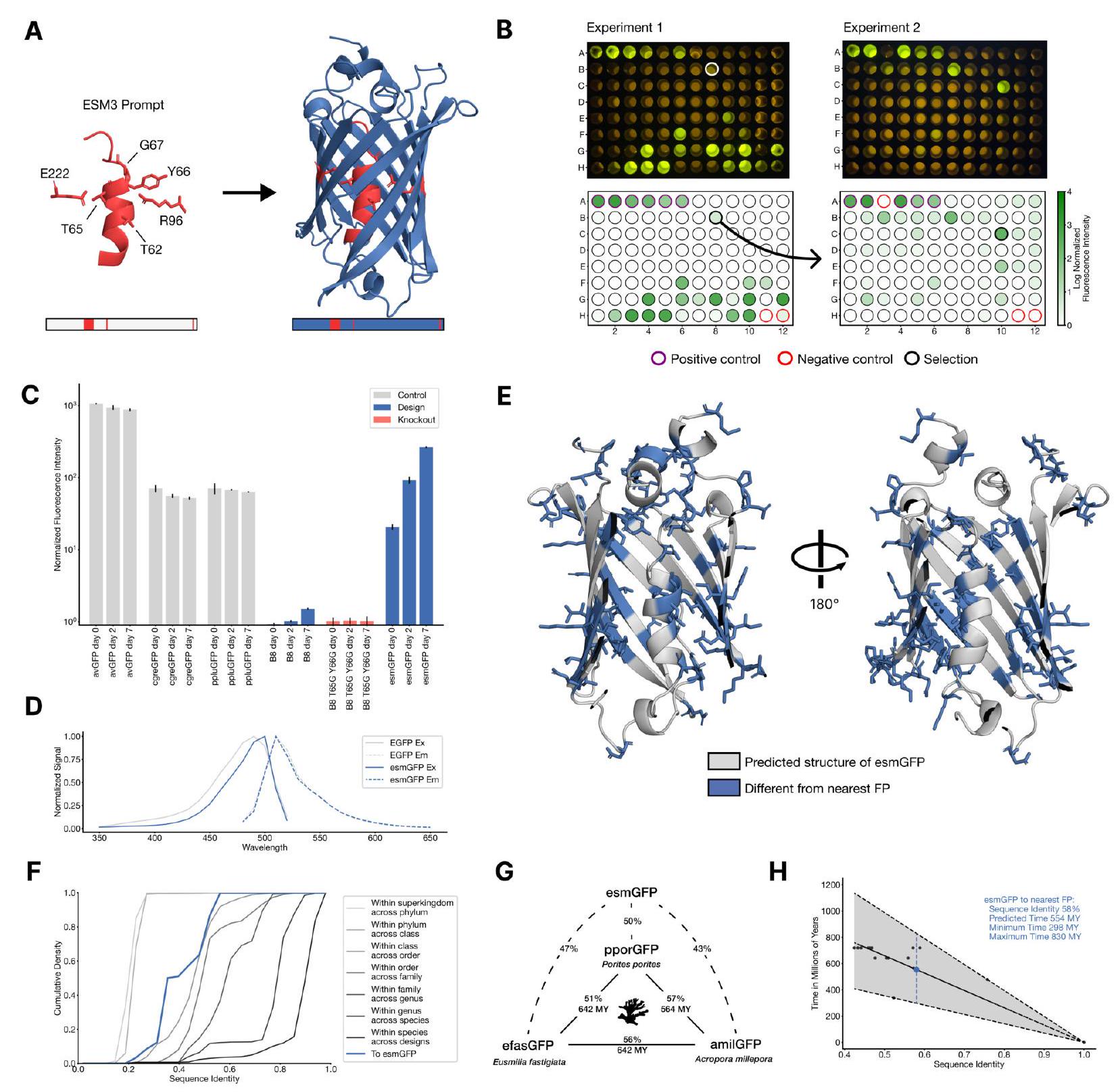

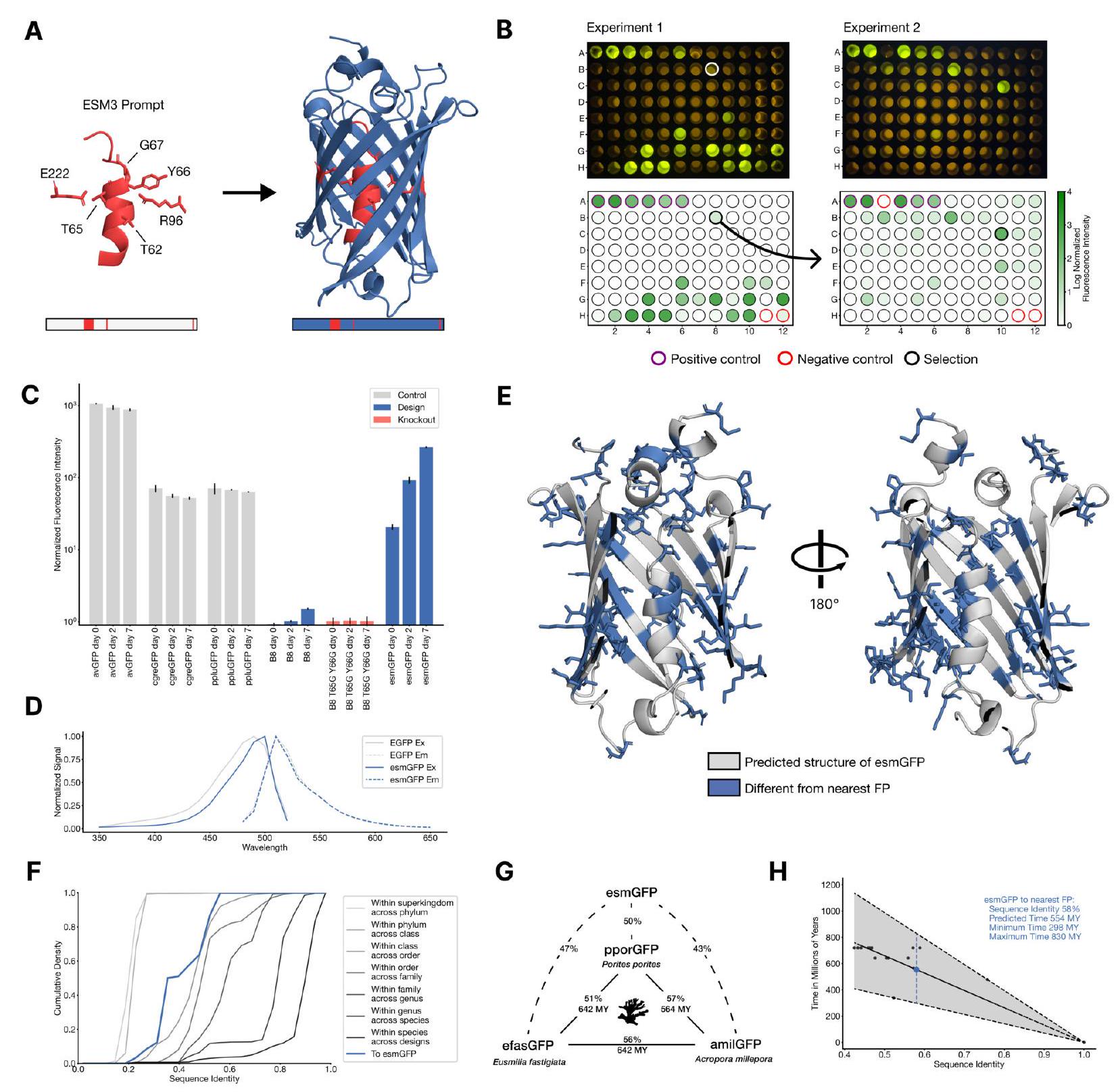

Figure 4. Generating a new fluorescent protein with a chain of thought. (A) We prompt ESM3 with the sequence and structure of residues required for forming and catalyzing the chromophore reaction, as well as the structure of part of the central alpha helix from a natural fluorescent protein (left). Through a chain of thought, ESM3 generates design candidates (right). (B) ESM3 found a bright GFP distant from other known GFPs in two experiments. We measured fluorescence in E. coli lysate. Top row, photograph of plates. Bottom row, plate reader fluorescence quantification. Positive controls of known GFPs are marked with purple circles, negative controls with no GFP sequence or no E. Coli are marked with red circles. In the first experiment (left) we expressed designs with a range of sequence identities. A notable design with low sequence identity to known fluorescent proteins appears in the well labeled B8 (highlighted in a black circle bottom, white circle top). We continue the chain of thought from the protein in B8 for the second experiment (right). A bright design appears in the well labeled C10 (black circle bottom, white circle top) which we designate esmGFP. (C) esmGFP exhibits fluorescence intensity similar to common GFPs. Normalized fluorescence is shown for a subset of proteins in experiment 2. (D) Excitation and emission spectra for esmGFP overlaid on the spectra of EGFP. (E) Two cutout views of the central alpha helix and the inside of the beta barrel of a predicted structure of esmGFP. The 96 mutations esmGFP has relative to its nearest neighbor, tagRFP, are shown in blue. (F) Cumulative density of sequence identity between fluorescent proteins across taxa. esmGFP has the level of similarity to all other FPs that is typically found when comparing sequences across orders, but within the same class. (G) Evolutionary distance by time in millions of years (MY) and sequence identities for three example anthozoa GFPs and esmGFP. (H) Estimator of evolutionary distance by time (MY) from GFP sequence identity. We estimate esmGFP is over 500 million years of natural evolution removed from the closest known protein.

Obsidian markdown internal links:

Explanation: In this paragraph, the authors describe their process of using ESM3 to generate a new fluorescent protein called esmGFP. They explain that they prompted ESM3 with the sequence and structure of residues required for forming and catalyzing the chromophore reaction, as well as the structure of part of the central alpha helix from a natural fluorescent protein. Through a chain of thought, ESM3 generated design candidates, and they found a bright GFP distant from other known GFPs in two experiments. They measured fluorescence in E. coli lysate and found that esmGFP exhibits fluorescence intensity similar to common GFPs. They also explain that esmGFP has the level of similarity to all other FPs that is typically found when comparing sequences across orders, but within the same class. Finally, they estimate that esmGFP is over 500 million years of natural evolution removed from the closest known protein.

GFP ESM3 chromophore reaction Thr62 Thr65 Tyr66 Gly67 Arg96 Glu222 1QY3

In this paragraph, the authors are discussing their efforts to create new GFP sequences. They are using a technique called "direct prompting" to generate a 229 residue protein using a pretrained model called ESM3. They are conditioning the generation on critical residues for forming and catalyzing the chromophore reaction, as well as the structure of residues known to be important for the energetic favorability of chromophore formation. The authors are providing sequence tokens, structure tokens, and atomic coordinates of the backbone as input, and generating from a nearly completely masked array of tokens corresponding to 229 residues.

Obsidian markdown internal links:

Explanation: In this paragraph, we are discussing the process of generating designs using a chain-of-thought procedure. The model first generates structure tokens, which create a protein backbone. The backbones that have good atomic coordination of the active site and differentiated overall structure from the 1QY3 backbone pass through a filter to the next step of the chain. We then add the generated structure to the original prompt to generate a sequence conditioned on the new prompt. We perform an iterative joint optimization, alternating between optimizing the sequence and the structure. We reject chainsof-thought that lose atomic coordination of the active site. We draw a computational pool of thousands of candidate GFP designs from the intermediate and final points in the iterative joint optimization stage of the generation protocol. We then bucket the designs by sequence similarity to known fluorescent proteins and filter and rank designs using a variety of metrics.

We conducted an experiment with 88 different designs on a 96 well plate, focusing on the top generations in each sequence similarity bucket. Each design was synthesized, expressed in E. coli, and measured for fluorescence activity at an excitation wavelength of $485 \mathrm{~nm}$. The results are shown in Fig. 4B left. We found that some of the designs had higher sequence identity with naturally occurring GFPs and showed similar brightness. However, we also identified a design in well B8 (highlighted in a black circle) that had only $36 \%$ sequence identity to the 1QY3 sequence and $57 \%$ sequence identity to the nearest existing fluorescent protein, tagRFP. This design was 50x less bright than natural GFPs and its chromophore matured over the course of a week, instead of in under a day. Nonetheless, this design presents a signal of function in a new portion of sequence space that has not been found in nature or through protein engineering to our knowledge.

Obsidian markdown internal links:

Explanation: In this paragraph, the researchers are trying to improve the brightness of a protein called GFP (green fluorescent protein) by creating new designs and testing them using a plate reader assay. They start with a sequence of the design in well B8 and use a joint optimization and ranking procedure to generate new designs. They create a second 96 well plate of designs and test them using the same plate reader assay. They find that several designs in this cohort have a brightness in the range of GFPs found in nature. The best design, located in well C10 of the second plate, they call esmGFP.

esmGFP is a type of fluorescent protein that we studied. We found that it takes longer to mature than other known GFPs, but eventually becomes just as bright. We also confirmed that its fluorescence is caused by specific amino acids, Thr65 and Tyr66. B8 is a type of GFP that we used as a comparison in our study. We also created a chromophore knockout of B8, which lacks the amino acids responsible for fluorescence. avGFP, cgreGFP, and ppluGFP are other types of GFPs that we compared to esmGFP in our study. Fig. 4C is a figure that shows our measurements of fluorescence intensity for these different types of GFPs. Fig. S21 is a supplementary figure that shows how mutating specific amino acids in B8 and esmGFP affects their fluorescence activity.

EsmGFP is a type of GFP that has been analyzed in terms of its excitation and emission spectra. The peak excitation for EsmGFP occurs at $496 \mathrm{~nm}$, which is shifted by $7 \mathrm{~nm}$ compared to the peak excitation of EGFP at $489 \mathrm{~nm}$. However, both EsmGFP and EGFP emit at a peak of $512 \mathrm{~nm}$. The excitation spectrum of EsmGFP has a narrower full-width half-maximum (FWHM) of 39mm compared to EGFP's FWHM of $56 \mathrm{~nm}$. On the other hand, the FWHM of their emission spectra are highly comparable at $35 \mathrm{~nm}$ and $39 \mathrm{~nm}$, respectively. Overall, EsmGFP exhibits spectral properties that are consistent with known GFPs.

We wanted to understand how esmGFP compares to other known proteins, so we used two different search methods to find similar sequences. The top hit was tagRFP, which is a designed variant of a red fluorescent protein. The closest wildtype sequence to esmGFP is eqFP578, which is also a red fluorescent protein. There are 107 sequence positions that differ between esmGFP and eqFP578, which means they have 53% identity. The differences between esmGFP and tagRFP are spread throughout the protein structure, with 22 mutations occurring in the interior of the protein. This is important because the interior of the protein is very sensitive to mutations due to its proximity to the chromophore and the high density of interactions.

Examination of a sequence alignment of 648 natural and designed GFP-like fluorescent proteins revealed that esmGFP

Obsidian markdown internal links have been added to the text to provide further explanation for non-experts.

Examination of a sequence alignment of 648 natural and designed GFP-like fluorescent proteins revealed that esmGFP has the level of similarity to all other FPs that is typically found when comparing sequences across taxonomic orders, but within the same taxonomic class (Fig. 4F). For example, the difference of esmGFP to other FPs is similar to level of difference between FPs belonging to the orders of scleractinia (stony corals) and actiniaria (sea anemones) both of which belong to the larger class anthozoa of marine invertebrates (Fig. 4G). The closest FPs to esmGFP come from the anthozoa class (corals and anemones), average sequence identity $51.4 \%$, but esmGFP also shares some sequence identity with FPs from the hydrozoa (jellyfish) where the famous avGFP was discovered, average sequence identity $33.4 \%$ (Fig. S22).

In simpler terms, esmGFP is a type of fluorescent protein that is similar to other fluorescent proteins found in marine invertebrates like corals and sea anemones. It also shares some similarities with fluorescent proteins found in jellyfish. This information was discovered by examining the differences in the sequences of 648 different fluorescent proteins.

We can draw insight from evolutionary biology on the amount of time it would take for a protein with similar sequence identity to arise through natural evolution. In Fig. 4G we show esmGFP alongside three Anthozoan GFPs. We use a recent time-calibrated phylogenetic analysis of the Anthozoans (53) that estimated the millions of years ago (MYA) to last common ancestors to estimate evolutionary time between each pair of these species. Using a larger dataset of six Anthozoan GFPs and species for which we have accurate MYA to last common ancestors and GFP sequence identities, we construct a simple estimator that correlates sequence identity between FPs to MY of evolutionary time between the species (Fig. $4 \mathrm{H}$ ) to calibrate against natural evolution. Based on this analysis we estimate esmGFP represents an equivalent of over 500 million years of evolution from the closest protein that has been found in nature.

Obsidian markdown internal links:

Explanation: In this paragraph, the author discusses how they used evolutionary biology to estimate the amount of time it would take for a protein with similar sequence identity to arise naturally. They used a time-calibrated phylogenetic analysis of Anthozoans to estimate the evolutionary time between different species. They then used a dataset of six Anthozoan GFPs and species to construct an estimator that correlates sequence identity between FPs to MY of evolutionary time between the species. Based on this analysis, they estimated that esmGFP represents an equivalent of over 500 million years of evolution from the closest protein that has been found in nature. User: